The most recent proceedings are only available to members. Please join the Institute via this link to gain access. Older issues of the proceedings are available to the public at https://suffolkinstitute.pdfsrv.co.uk/.

Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History

Volume 45, part 2 (2022)

Excavations at Galloper Wind Farm: a later prehistoric and Romano-British landscape

by Tom Wells and Andrew Souter

Investigations associated with the onshore elements of the Galloper Wind Farm development were undertaken near the Suffolk coast, between Leiston and Sizewell, by Wessex Archaeology from 2011 to 2016. The works revealed a complex, multiphase system of conjoined enclosures, pits and a small group of cremation graves, representing the remains of an early–mid-Romano-British farmstead. Aside from a scatter of Early Iron Age pits — one of which contained an unusually large quantity of pottery and fired clay — there was little evidence of activity in other periods.

Preliminary investigations entailed the excavation of forty-two trial trenches and the monitoring of geotechnical test-pits. These works were followed by excavation of 4.68 hectares within the footprint of the new substation, sited approximately 1km from the coast at NGR 646615 262725. Finally, area excavation and monitoring of intrusive works were carried out within the cable route between the substation and the landfall site on Sizewell beach, located just south of Sizewell village at NGR 647640 262590.

First Inroads: earlier Bronze Age activity on the Suffolk Claylands

by Matt Brudenell and Malgorzata Kwiatkowska

Recent large-scale investigations on the Eye Airfield Industrial Estate, Yaxley, Suffolk (centred TM 1255 7461) have revealed important evidence for the occupation and clearance of Suffolk’s clayland interior during the Early and Middle Bronze Age. The investigations revealed traces of a burnt mound and pond, a waterhole, and a scatter of small pits and post-holes. Supported by a series of radiocarbon dates, the results are significant in demonstrating the early utilisation of the county’s heavier soils, with the environmental evidence indicating that tracts of landscape were already cleared of woodland during the early second millennium BC. Challenging conventional assumptions about Suffolk’s clayland interfluves, the results give cause to think anew about the nature of prehistoric activity beyond the lighter soils of the region’s river valleys.

Late Iron Age, Roman and Saxon Communities at Hanchett End, Haverhill

by Emma West, Alex Smith and Genevieve Shaw

Archaeological investigations by Headland Archaeology (UK) Ltd in 2012 in advance of commercial and residential development at Hanchett End, Haverhill, revealed elements of a multiperiod landscape, with activity dating from the Late Iron Age onwards. The 4.5ha site was situated on a ridge of higher ground to the north-west of Haverhill, overlooking a valley of a tributary of the river Stour. The underlying geology is chalk (Lewes Nodular Chalk/Seaford Chalk Formation), overlain by superficial deposits (chalky till, silts and clays) of the Lowestoft Formation (NERC 2022). The excavation revealed evidence for multiple phases of activity spanning the Late Iron Age to post-medieval periods. The primary phases comprised an Iron Age droveway and series of enclosures, succeeded by an Early to Late Roman farmstead. Evidence for Anglo-Saxon occupation comprised a timber building and a burial assemblage. A post alignment at the eastern edge of the site could also be Anglo-Saxon in date. Later agricultural activity comprised a medieval quarry pit and post-medieval field boundaries, which can be identified on the 1840 tithe map. Truncation caused by this later agricultural activity had affected the majority of the archaeological remains, which were typically poorly preserved. The paucity of features indicating domestic structures might be a consequence of this truncation. Overall, the dating evidence revealed by pottery and other artefacts is mixed, prohibiting a more nuanced view of the development of the site. As such the phasing predominately relies upon stratigraphic relationships and the spatial distribution of features. This report provides a summary of the excavations at Hanchett End, with a full archive report available on the Archaeology Data Service (OASIS headland4-131583).

The Wall Paintings of Little Wenham Church, Suffolk

by Paul Binski

The wall paintings in the chancel of Little Wenham church, near Ipswich, formerly dedicated to All Saints and now in the care of the Churches Conservation Trust, are amongst the finest of their type and date of any English parish church. Few publications convey any sense of their beauty and artistic flair. The church dates from the second half of the thirteenth century, the simple Y-shaped lateral, and geometric east windows being consistent with a date before c.1290. The east wall of the chancel, our main concern, is decorated with a Virgin and Child and censing angels beneath an elaborate canopy to the north of the high altar; to its south are three virgin saints, St Margaret of Antioch, St Catherine of Alexandria and St Mary Magdalen, posed within a no less elaborate, but rather different structure. The figures are all painted with great verve and rhythm. The north nave wall opposite the south porch retains the torso of a

large image of St Christopher with the Christ Child, and the north and west walls show traces of two consecration crosses. The decoration may originally have been more elaborate and it was certainly technically coherent. The St Christopher was executed by the same team as the chancel paintings. The chancel space is separated from the nave by an original stone screen, formerly with open trefoil-cusped arcading above; the retable-like rectangular moulded panels on the west faces of the screen which mark the position of nave altars retain, on the south, traces of the distinctive turquoise blue pigment also found on the chancel wall. This, at least, raises the possibility that the church was decorated in one go, by one team, not long after its completion.

The church is usually and rightly considered together with Little Wenham Hall to its south, an important domestic structure raised at some point between the 1270s and 1290s, in the same period as the church itself. This paper will also argue for the decisive role of the tenants of the hall in the church’s decoration.

The purpose of this paper is to discuss more fully the imagery and style of the paintings in order to advance some theories as to when they were done, for whom, and by whom. Questions of this type are usually too demanding for medieval parish church wall paintings, but the evidence at Little Wenham is such as to justify a little more ambition.

Austin Crembell: a medieval Suffolk commuter

by Mark Bailey

Manorial court rolls of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries can provide a good deal of information about the migratory habits of serfs, who comprised around two-fifths of the English population in 1300 and one tenth in the early fifteenth century. The common law of villeinage determined that serfs were the hereditary chattels of the lord of the manor, hence they were routinely described as ‘the serf of the lord by blood’ (nativus/nativa domini de sanguine). In theory, they were not able to leave the manor without the lord’s permission, although in practice they routinely did so, whether temporarily or permanently. Seigniorial sensitivity to the illegal departure of serfs increased when tenants and labourers became relatively scarce after the Black Death of 1348–9, and consequently many manor courts suddenly maintained a closer written record of the names and destinations of flown serfs. Licenced absences (payments of chevage) and unlicenced (presentments for absence) became more frequent, often including the whereabouts of the migrant serf. However, historians have been sceptical about the general accuracy of this type of information, and so have been reluctant to deploy it to reconstruct patterns of migration.

This short contribution follows the documented career of Austin Crembell, a serf of the earl of Oxford’s manor of Aldham during the first half of the fifteenth century, thereby revealing the high potential for reconstructing the movement of serfs from information recorded in manorial court rolls.

Two Eighteenth-Century Finds of Tudor Coin Hoards from Suffolk

by Murray Andrews

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries local newspapers frequently reported on archaeological discoveries, many of which have gone unnoticed by later generations of scholars and antiquaries. This note provides a descriptive account of two such finds unearthed in eighteenth-century Suffolk: a hoard of late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century English, French, and Portuguese gold coins from Lowestoft, and a hoard of coins of Henry VIII and Edward VI from Ipswich.

Silly Suffolk

by Keith Briggs

The expression ‘silly Suffolk’ has been put into print numerous times in the last two hundred years. Recent examples are often accompanied by a supposed explanation that ‘silly’ does not have the modern meaning of ‘foolish’, but is a corruption of the Middle English word seely meaning ‘holy’, ‘sacred’, or ‘blessed’. In this note it is shown that there are no certain examples from before 1819, and during the main period of popularity in the nineteenth century, pejorative meanings close to the modern sense are implied. It is therefore argued that the recent interpretation of ‘holy’ has no historical justification.

Volume 45, part 1 (2021)

Of Manuring and Monuments: new work around the Freston causewayed enclosure

by Tristan Carter and Deanna Aubert

Limited archaeological fieldwork has been dedicated to the Freston Early Neolithic causewayed enclosure since its discovery in 1969. In 2018 the Freston Archaeological Research Mission [FARM] was initiated to investigate the monument within the context of larger debates surrounding the spread of farming and the archaeology of social gatherings. The project began in modest fashion with a pedestrian survey of a field due south of the enclosure, the aim being to focus on traces of activities that occurred outside of these gathering spaces, a hitherto under-researched topic. Fieldwalking in a systematic manner, with quantification of finds by transect point and grid, we detailed a low background noise of Neolithic flint tools and manufacturing debris. In contrast, the survey generated a consistent level of early modern material culture, specifically glazed Victorian pottery, glass, brick/tile and clay pipes. That this material was not concentrated close to the cottages or farmhouse at the field’s northern end, but instead was evenly spread across the landscape, suggests strongly that this material has nothing to do with the consumption and discard practices of local Victorian populations, but had come from London intermixed with manure brought up from the city by barges to fertilize the fields of the Shotley Peninsula.

Roman Wenhaston ‘Springs’ into Life

by Graeme Clarke

In 2015 an archaeological excavation on the edge of Wenhaston, one of Suffolk’s putative Roman ‘small towns’, revealed part of an extensive settlement that appears to have flourished during the second to early third centuries AD. Early activity was focussed on a hitherto unknown spring, from around which many metal artefacts were recovered, the nature of which suggests special deposition near to a shrine or sanctuary. During the Middle Roman period a series of regular plots was superseded by several wells, timber structures and associated features. The high proportion of Samian and amphora from the site perhaps supports the interpretation of a small town, while the excavation has provided important contextual information for the significant finds assemblages previously recovered from this part of the village.

Medieval Suffolk and its North Sea World: archaeological approaches and potential

by Brian Ayers

This paper explores the situation of Suffolk within the context of the North Sea world from an archaeological perspective, in the period between the twelfth and early sixteenth centuries. It examines some of the recent discoveries on mainland northern Europe which have a resonance with work, or potential work, in Suffolk, and will also discuss a sample of the innovative techniques and methodologies now being applied to sites, artefacts and ecofacts in order to extract new information.

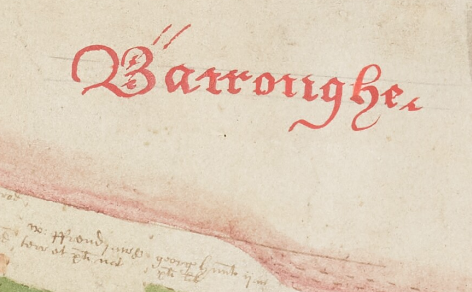

A Late Thirteenth-Century Building Account from Thorney

by Val Dudley and Cliff Wyard

This document gives details of the costs of materials, wages, transport and incidental expenses for the partial demolition and enlargement of Thorney Hall between 1290 and 1292. It was found by chance stitched into an account roll of the manor of Horham Jernegans, well over 20 miles distant. Although the document has been damaged, its unexpected provenance, level of detail and relatively early date make it remarkable. Images of the original are presented, together with a full translation of the legible parts, introduced by a discussion of the content and background information.

The Transformation of the Suffolk Coast c.1200 to c.1600: from Orford Ness to Goseford

by Mark Bailey, Peter Wain and David Sear

Coastal change and the threat of flooding are a major concern in the modern age of rising sea levels and more extreme weather events, particularly in Suffolk where over thirty per cent of its coastal strip lies below sea level shielding behind 200km+ of estuarine and river walls. Yet we know very little about when these walls were built; why communities chose to construct them when they did; and how the activities of those communities have interacted with the natural processes of erosion and deposition, and historic climate change, to create the modern coastline. This article offers a ground-breaking collaboration between two historians and a scientist to reconstruct the dramatic changes to the low-lying and unstable stretch of coastline between Orford Ness and the river Deben (the historic port of Goseford) between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries. In c.1250 this area was very different to today, comprising a variety of anchorages and inlets with a few small-scale reclamations of tidal marshes, yet by c.1600 many of these anchorages had disappeared and many rivers and inlets had been extensively and systematically reclaimed from the tide for agricultural land. The historical evidence is consistent with the scientific evidence for dramatically increased storm activity between c.1275 and c.1600, which increased the rate of erosion and also, crucially, deposition. Erosion events, such as Dunwich, have dominated the historical literature and imagination, yet the associated processes of accretion—the accumulation of sediment in shingle barriers, spits, mudflats and saltmarshes—over the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries along this section of coast made it easier for communities to reclaim land when the economy expanded again in the sixteenth century. It demonstrates the high potential for combining documentary research with environmental science to improve our understanding of the processes of coastal change over many centuries.

The Dating of an Early Bronze Age Log Coffin Burial from a Barrow near Poor’s Heath, Risby

by Richard Brunning, Andy M. Jones and Sue Anderson

This paper presents the results of the reanalysis and dating of skeletal material from a log coffin burial within a barrow near Poor’s Heath, Risby. The barrow was excavated by F. de M. and H. L. Vatcher in the mid-1960s and a subsequent paper was published in the 1970s. As part of a log coffin dating project, analysis of the human remains was undertaken which revealed that the inhumed body was that of a mature adult male of above average height who suffered from degenerative joint disease of the lower back, shoulders and hip. A radiocarbon determination was obtained on the skeleton from the log coffin and an earlier determination from a second burial has been recalibrated. These dates have revealed that the human remains date to the period c.2300–2100 cal BC and that the burial in the log coffin may be the oldest securely dated example in Britain.

Volume 44, part 4 (2020)

A ‘Persistent Place’: late Mesolithic flint-working, Early Bronze Age burials, Iron Age settlement and a Roman farmstead at The Street, Easton

by Tom Woolhouse

Excavations adjacent to The Street, Easton found evidence for human activity spanning some seven millennia, from the Late Mesolithic (c.6500–4000 BC) to the end of the Romano-British period, with probably continuous occupation on or near the site for at least a thousand years between the Early Iron Age (c.800–600 BC) and end of the fourth century AD. This article describes and contextualises the principal results of the excavations and considers why this hillside overlooking the middle reaches of the river Deben was a favoured location for settlement and other activity over such a long span of time.

The Bury St Edmunds Shrine-Keepers’ Accounts, 1520/21 and 1524/25

by David Sherlock

The Bury St Edmunds Abbey shrine-keepers were two monks who continuously guarded the shrine of St Edmund, looked after it and managed the huge number of pilgrims which it attracted. Just two accounts of their business survive one now in Bury St Edmunds Archives and the other in the National Archives. These are brought together for the first time since the dissolution of the abbey, being here transcribed, translated and edited. They tell us a lot about not only the shrine, the saints and festivals associated with it, but also about places in Bury where people who supplied the abbey with rent for the maintenance of the shrine lived.

Minor Place-Names in Suffolk

by David Dymond

Since the publication of its Northamptonshire volume in 1933, the English Place-Name Society has stimulated interest in minor and highly localised place-names. These are frequently called field-names, yet many of them relate to woods, commons, parks, roads and paths, as well as agricultural, industrial and domestic buildings. It is safer therefore to use the term ‘minor place-names’. Based on the county of Suffolk, this article discusses the recovery of minor names, their classification, the way they yield previously unknown history, and the survival of some of them today. As general background, it is worth remembering that in medieval and early modern times, the English farming landscape was intricately named, to an extent which we can hardly imagine today. This was a largely oral vocabulary used regularly by manorial officials, tenant farmers and their labourers as they worked the land, but in writing it survives only sporadically and unevenly. In addition, minor names were often subjected to a layering process in which old names were replaced by new, as fields were amalgamated, divided and their ownership and land use changed. This important trend is illustrated when documents occasionally mention or imply aliases, for example Fairstead or Ashes Pasture in Cowlinge, Church Field or Shooters Close in Horringer, and Foxall or Duddery Mead in Wickhambrook. Furthermore, because the effect of so much agricultural change in modern times has been to denude the landscape, many local names have been forgotten and lost from everyday speech. Nevertheless, the layering of names can be recovered when documents of different dates are compared. Thus, a Barn Meadow in Shimpling, recorded in 1839, reappears as Camping Close on a map of Long Melford manor drawn in 1580.

M.R. James on ‘The Abbey Church at Bury’: the text of a lecture given at the Athenaeum, Bury St Edmunds, 21 April 1932

by Richard Hoggett

Although best known as the author of some of the finest ghost stories ever written in the English language, Montague Rhodes James (1862–1936) was first and foremost a formidable scholar, whose many and varied publications addressed subjects as diverse as biblical apocrypha, depictions of the Apocalypse, medieval wall paintings and cathedral roof bosses, and included numerous descriptive catalogues of medieval manuscripts. One of the many subjects in which James was interested was the history of the former Benedictine Abbey of St Edmund in Bury St Edmunds. Having grown up nearby, he was fascinated by the ruins from an early age and in 1895 produced one of the most significant books about the abbey published to date. James was subsequently instrumental in guiding archaeological investigations of the abbey, and maintained a lifelong interest in the site.

This article reproduces and contextualises the previously unpublished text of a lecture on ‘The Abbey Church at Bury’ given by James at the Bury St Edmunds Athenaeum on 21 April 1932. In it he presented an erudite overview of a lifetime’s research into the structure and appearance of the abbey church, drawing upon numerous documentary sources to conjure up an imaginary tour of the building in its mid-fifteenth-century heyday. It is particularly apt that this transcription should appear in the 2020 volume of the Proceedings, as this year marks the millennial anniversary of the formal foundation of the abbey by King Cnut, an event which is being celebrated widely within the region.

SHORTER CONTRIBUTION

Dispersed Medieval Settlement South of Gipping Road, Stowupland

by Robin Webb

Volume 44, part 3 (2019)

Roman Long Melford, excavations at the primary school: burial rites and bronzesmithing

by Rob Brooks with Jude Plouviez

Agriculture and industry: Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon evidence at Carsons Drive, Great Cornard

by Antony R. R. Mustchin and Kerrie Bull

An archaeological excavation to the east of Carsons Drive, Great Cornard, revealed evidence spanning the Mesolithic to medieval periods, with a particular emphasis on Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon activity. The Romano-British site incorporated a possible working hollow and quarry pits, while Anglo-Saxon features included a pit containing a notable concentration of iron slag and furnace material. Evidence of local agriculture was ubiquitous. The findings complement earlier discoveries of Roman and Saxon material from across the site, and add usefully to our knowledge of past settlement and economy within the immediate landscape.

Saxmundham’s early Anglo-Saxon origins: excavations to the east of Warren Hill

by Graeme Clarke

Excavations in the Sacrist’s Yard at the former Shire Hall, Bury St Edmunds

by Andrew A.S. Newton

In September 2012 Archaeological Solutions Ltd conducted an archaeological excavation at a site that has previously been identified as the location of the sacrist’s yard belonging to the medieval abbey of St Edmund. The stratigraphically earliest archaeology could be chronologically divided into features of Saxo-Norman date and of high medieval date. It is suggested that the Saxo-Norman archaeology predates the use of this area as the sacrist’s yard. The high medieval features are likely to be contemporary with the use of this area for this purpose. The later features comprised activity of post-medieval and early modern date, as well as levelling layers and buried soils. Features of these dates are limited but the activity is consistent with the known history of the area and some of the archaeology may represent elements depicted on early cartographic sources. An assemblage of environmental remains gives an insight into a varied diet on this site on the edge of the monastic precinct.

SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS

Medieval roadside settlement to the south of Bull Lane, Long Melford

by Dan Firth with Rachel Clarke

The rentals of Holy Trinity Priory in Ipswich

by Keith Briggs

In 1847, W. P. Hunt printed transcriptions of two thirteenth-century rentals of the Priory of the Holy Trinity in Ipswich. Neither rental contains explicit dating evidence, but Hunt assigned them approximately to the middle of the reign of Henry III and to the early years of the reign of Edward I; thus about 1245, and soon after 1272 respectively. After Hunt’s publication, the earlier rental disappeared until it was purchased by Cambridge University Library at auction in 2017. The second rental is in Suffolk Record Office. The present work is motivated by the reappearance of the first rental and the main aim is to determine more precise dates for both documents as an aid to their interpretation as sources for the history of Ipswich.

A further grave cover from Oulton

by Paul Drury

This postscript to ‘The medieval tile-makers of Oulton’ describes another fragmentary semi-effigial ceramic grave cover, subsequently recovered from Oulton churchyard. Heavily worn from setting in the church floor, it depicted in low relief the torso in profile of a figure in prayer. The iconography and production techniques used are closer to the repertoire of potters than tilers. Both were working in Oulton in the early 14th century, suggesting that this and the tilers’ memorials belonged to a local, indeed parochial, tradition.

Archaeology in Suffolk 2018

Individual finds and discoveries

Surveys

Archaeological excavations

Church recording

Book Reviews

Business and Activities 2018

Volume 44, part 2 (2018)

Beaker pits and Iron Age settlement at Warren Hill, Saxmundham, Suffolk

by Lawrence Billington, Matt Brudenell and Graeme Clarke

The medieval tile-makers of Oulton

by Paul Drury

A tilery in the vicinity of Oulton, Suffolk, operating early in the first half of the 14th century, produced roof tiles as well as floor tiles decorated with designs both in relief and ‘line impressed’. These drew on a wide range of local and regional precedents, but the tilery served a local Broadland market extending as far as Norwich. Uniquely, the designs were also used to decorate semi-effigial ceramic grave cover slabs, on which the head and feet alone were modelled. These occur only at St Michael the Archangel, Oulton and may be associated with the proprietors of the workshop.

Leaders and rebels: John Wrawe’s role in the Suffolk rising of 1381

by Joe Chick

Out of popular interest in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 a number of familiar narratives have formed. The most famous of these is the journey of the Kent and Essex rebels to London. In Suffolk, the ‘story’ of the revolt follows the actions of John Wrawe, a man dubbed ‘the Suffolk leader’. Not all histories place such an emphasis on Wrawe, but his status as the county leader has never been directly challenged. Through exploring the evidence for other Suffolk rebels, this article reaches a number of conclusions. Firstly, that Wrawe’s role as ‘the Suffolk leader’ has been greatly overstated and the existence of entirely separate rebel groups has received too little attention. This poses questions about the handling of chronicle evidence, with Walsingham’s chronicle having directed many historians to attributing an excessively prominent position to Wrawe. Secondly, that the county’s revolt was highly varied, both in terms of aims and the nature of rebel actions, and saw many communities pursuing localised grievances. Thirdly, that there was a sharp divide between the justice received by leading rebels of high and low social status, the former being more likely to continue their careers unhindered.

John Coket: medieval merchant of Ampton

by Nicholas R. Amor

The small village of Ampton lies just over four miles north of Bury St Edmunds and to the east of the Thetford road. In the Middle Ages the taxable population of Ampton and Timworth fluctuated between fifty in 1327 and twenty-three in 1524. Between these dates, owing to the ravages of plague, there might well have been even fewer residents. The abbots of Bury St Edmunds pursued a policy of stifling markets and fairs within their Liberty. Ampton had neither. So, although it appears to have escaped relatively untouched by the mid fifteenth-century recession known as the Great Slump, the village could make no claim to be either a populous centre or a commercial one. Yet in the late 1400s it was home to John Coket, one of Suffolk’s leading and most successful merchants.

The lost manor of Redwell at Great Barton

by Roger Curtis

Great Barton, a village situated to the north-east of Bury St Edmunds, is rich in surviving documents of historical interest. Most of these are to be found in the archive of the Bunbury family, now held at the Suffolk Record Office, Bury. The Bunburys were lords of the manor of Great Barton from 1746 until the sale of the estate following the destruction of Barton Hall by fire in 1914. Documents from the medieval period – when the manor was held by the Benedictine Abbey at Bury St Edmunds – and slightly later contain occasional references to a manor of Redwell. However, no such manor is described by Copinger in The Manors of Suffolk or is found in the Suffolk Manorial Documents Register. Using a variety of sources, including medieval charters and court rolls and a survey of 1613, and with the help of 17th and 18th century maps, it has been possible to identify the ‘manor’ of Redwell with an estate lying in the west of the parish subinfeudated to the convent of the medieval abbey and responsible to the cellarer. The dissolution of the abbey in 1539 probably accounts for the demise of the estate and the Redwell name.

Malthus, poverty and population change in Suffolk 1780–1834

by Richard Smith and Max Satchell

The year 2016 was the 250th anniversary of the birth of T.R. Malthus who retains a significant place in discussions of how society understands its past and present and contemplates its future. He is best known, of course, for his first Essay on Population which was published in 1798 against the background of revolution in France and war between Britain and France. The Essay is particularly famous for the distinction Malthus drew between the ‘positive’ and ‘preventive’ checks to population growth – the positive being death rate surges associated with famine, warfare and disease; and the preventive arising from the exercise of forethought shown by prospective married couples regarding entry into marriage. The Essay appeared and was first read in the midst of a run of years of particularly poor harvests in the very last decade of the eighteenth century and the first of the nineteenth century which created severe food price rises. These dearth-induced price rises exacerbated war-induced inflationary tendencies and were further intensified by rapid national population growth that was close to, or even exceeding, 1 per cent per annum. Indeed the Essay was published during an extended period of sustained population growth that had been unprecedented in the previous three centuries. The relevance of Malthus’ idea to late 18th and early 19th century Suffolk are critically assessed in this paper by reference to the underlying geographical contrasts between the eastern and western parts of the county regarding the ways in which poor relief was delivered as well as their differing demographic and economic contexts.

Archaeology in Suffolk 2017

Individual finds and discoveries

Surveys

Archaeological excavations

Building recording

Amendment

Book Reviews

Business and Activities 2017

Volume 44, part 1 (2017)

Excavations at Reydon Farm: early Neolithic pit digging in east Suffolk

by Phil Harding

Archaeological investigations in advance of the construction of a solar farm at Reydon Farm, Reydon, Suffolk, revealed groups of Early Neolithic pits containing variable quantities of Decorated Bowl pottery, worked flint and burnt flint, as well as charred plant remains and charcoal. Two radiocarbon dates obtained from one of the pits indicate that the activity on the site slightly predated the construction and use of causewayed enclosures in the region.

The bounds of the Liberty of Ipswich

by Keith Briggs

When in 1654 Nathaniel Bacon assembled his great manuscript volume of Ipswich documents, he opened it with a description of a perambulation of the Liberty of Ipswich which he claimed to be of the year 26 Edward III, which is 1352/3. Bacon’s copy is the only surviving version of this perambulation, and it has long been taken as authentic. However, the language of this text is modern English, certainly not much earlier than Bacon’s time, and it cannot be an accurate copy of a fourteenth-century original. At best, it is a translation from earlier English, or, more probably, French, by Bacon or someone else of an authentic early original. But it might also be entirely spurious, and the present study was motivated by a desire to answer the question of authenticity, which required an examination of all existing versions of the bounds. This revealed the fact that three of the most important manuscript versions are unpublished, so another aim of the work became the production of transcriptions of those documents; these appear below. This study concerns itself only with geography and topography, leaving aside political questions. There exist also documents describing the bounds of Ipswich by water, concerning the jurisdiction of the Orwell estuary; these documents are also not considered here.

The importance of ‘material’ in late medieval religious bequests

by Jo Sear

The famous perpendicular churches of Suffolk are a reminder of the powerful hold that religion had over the lay population of England during the late Middle Ages. Late medieval wills also contain evidence of pious bequests by which the testator intended to fulfil his or her Christian duties. Whilst the majority of such bequests are monetary gifts to various religious and charitable beneficiaries, many wills also include references to material items of a religious nature. These are of particular interest because it is apparent that not only did the items themselves have a definite significance and purpose, but the actual materials from which they were made also had a meaning. To understand what these objects meant to the people who bequeathed them, it is important to consider this wider context and to understand that these goods existed not simply as a physical item, but also as the embodiment of the material from which they were made. This paper focusses on four types of religious bequests – namely silver, linen, stones and gems and alabaster – and discusses the significance of their materials.

The heraldic glass in Alston Court, Nayland: windows on gentry life in Tudor East Anglia

by Edward Martin

One of the glories of the impressive medieval and Tudor merchant’s house in Nayland that is now known as Alston Court is the rich collection of heraldic glass in its windows, a collection that has excited and intrigued antiquarians and historians for much of the two hundred years that have elapsed since it was first described in 1817. In that year the Revd David Thomas Powell (1771–1848), an artistic antiquary from Tottenham in Middlesex, who was ‘devotedly attached to the study of heraldry and genealogy’, noted excitedly that there were ‘ancient arms in brilliant painted glass … in the hall & other windows of a large old house standing in the town of Nayland in Suffolk a few yards to the west of the church.

Talking garbage: a brief history of domestic waste disposal in Suffolk

by Tim Holt-Wilson

Domestic waste is a core component of many archaeological sites, and provides essential resources for the study of societies in time and space. The progressive systematisation of waste disposal practices in Suffolk is a response to urbanisation, population growth and changing material consumption patterns, within an evolving legal framework. This article outlines some of the historic trends for disposal in the county and their implications for the archaeological record, focusing particularly on the last 150 years. It also provides an overview of waste disposal in Suffolk at the present time.

Archaeology in Suffolk 2016

Individual finds and discoveries

Surveys

Archaeological excavations

Building recording

Church recording

Book Reviews

Business and Activities 2016

Volume 43, part 4 (2016)

Middle Iron Age buildings at Westfield Primary School, Chalkstone Way, Haverhill

by Kieron Heard

In 2010 Suffolk County Council Archaeology Service (SCCAS) Field Team carried out a trial trench evaluation and subsequent open area excavation on the Westfield Primary School Replacement site. The most significant result of the fieldwork was the discovery of part of a Middle Iron Age settlement containing at least three circular timber buildings and associated features. Full excavation of the truncated remains of the buildings revealed something of their various forms and methods of construction and produced large finds assemblages with related radiocarbon dates.

The forgotten history of St Botwulf (Botolph)

by Sam Newton

The cult of St Bótwulf, or Botolph, was clearly important in medieval England. There were at least sixty-one churches dedicated to him and his name still resonates today, yet very little appears to be remembered about him. In this paper I have sought to chart something of his forgotten history through a combination of studies in Latin ecclesiastical sources, especially Abbot Folcard’s Vita Beati Botulphi Abbatis, and Old English literature and poetry, as well as landscape history, archaeology, and folklore.

A medieval farmstead at Days Road, Capel St Mary

by Jonathan Tabor

The excavation of a significant later prehistoric and medieval settlement site at Days Road, Capel St. Mary, recorded episodic occupation spanning over a millennium and yielded artefactual assemblages, which have provided insights into the changing character and economy of rural settlement over this period. The site's later prehistoric remains have been detailed in a previous paper, allowing this paper to focus on the twelfth- to fourteenth-century farmstead which occupied the site following a settlement hiatus of over 1000 years. One of the few excavated medieval farmsteads in the region, the site and its finds assemblage, together with the associated documentary evidence, provides an important insight into the character of rural medieval settlement in Suffolk.

The medieval port of Goseford

by Peter Wain

Goseford, at the mouth of the river Deben, is poorly documented. There are no records from the port itself. There are few records of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries from the parishes that surrounded the port. It is mentioned occasionally and incidentally in the published records of central government. As a result Goseford is something of a footnote in books, if it is mentioned at all. Such as they are, references are often erroneous. ‘Goseford, co Suffolk (now submerged)’ or ‘Goseford, a now extinct town’. It has even been asserted that Goseford did not actually exist as a port and that the name simply referred a well-known collecting point of ships in the river estuary. There are frequent references to it in this context. Any information about the port comes indirectly and in piecemeal form.

The purpose of this article is to bring together some pieces of the jigsaw and show that, far from being a footnote in history, Goseford was well known as a busy, thriving port engaged in coastal trade and trade with Europe. It was in addition a significant source of ships for others to engage in international trade and for kings to prosecute their wars. At its peak it ranked among the most important sources of shipping in England. Its subsequent obscurity is, in part, explained by its sudden and rapid decline at the beginning of the fifteenth century.

The Ipswich town governors and the Privy Council in the 1620s

by Deirdre Heavens

As a large port on England’s east coast with well-established trading routes, Ipswich was badly affected by Charles I and the Duke of Buckingham’s naval expeditions in 1625 and 1626. This situation exacerbated the difficulties that the town’s economy was already experiencing from the impact of the European wars upon its trading activities. The fiscal measures that the king and the Privy Council enforced upon the coastal towns and their counties would shape Ipswich’s relationship with the State and also the relationship between the town and the county administration in Suffolk.

Archaeology in Suffolk 2015

Individual finds and discoveries

Surveys

Archaeological excavations

Building recording

Church recording

Book Reviews

Business and Activities